By Kelly Murphy-Redd

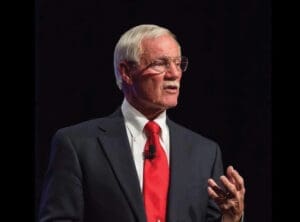

Local resident Ed Hubbard joined the United States Air Force in 1955. He flew the RB66 Destroyer while stationed in England and spent nine months in France. One Saturday afternoon, he received orders to deploy to Thailand. Ed dropped off his family in the U.S. and went to the Philippines for three weeks of survival school. He was stationed at Takhli Air Base in Thailand flying into Vietnam. Thirty days later, he was shot down by a surface to air missile. Ed spent eight hours in the jungle before he was captured. He spent six years, seven months and 12 days in prison.

Local resident Ed Hubbard joined the United States Air Force in 1955. He flew the RB66 Destroyer while stationed in England and spent nine months in France. One Saturday afternoon, he received orders to deploy to Thailand. Ed dropped off his family in the U.S. and went to the Philippines for three weeks of survival school. He was stationed at Takhli Air Base in Thailand flying into Vietnam. Thirty days later, he was shot down by a surface to air missile. Ed spent eight hours in the jungle before he was captured. He spent six years, seven months and 12 days in prison.

In prison, two Cuban interrogators controlled 10 Americans in one building. One day, guards threw a new American prisoner on the floor. He was comatose, couldn’t speak or eat, and was beaten badly. After three days, they had to do something.

In prison, two Cuban interrogators controlled 10 Americans in one building. One day, guards threw a new American prisoner on the floor. He was comatose, couldn’t speak or eat, and was beaten badly. After three days, they had to do something.

The group decided to force-feed him twice a day. They did this for a year. At this time Ed had a broken jaw, lost 75 pounds, and boils all over his body. He was supposed to die. Feeding this comatose American taught him something. He cites a quote from the book, Man’s Search for Meaning: “Life without a purpose is no life at all.” Keeping this man alive kept Ed alive.

Feeding took one-and-a-half hours. Four people held him down. They held his nose shut and put a stick in his mouth. He had to swallow to breath. He regained consciousness one time and was almost normal, but in 1970, he died.

Ed was put in solitary confinement twice for 30 days each and once for 91 days. He wasn’t cooperating with the indoctrination and wrote something the guards didn’t like. He was beaten every day for 28 days.

In solitary, Ed paced the floor all day talking to himself, convincing himself he would be O.K. He decided if he changed the way he viewed the situation, he could change how he dealt with it. He tried to think of who had it worse than he did. His answer was orphans, because they don’t know who their parents are. He decided 90% of people in the world had it worse than he did.

He promised himself he would survive no matter what. Ed says a pity trap is where you go to die. He vowed he would never feel sorry for himself again and would never have another bad day as long as he lived.

In January of 1973 the peace treaty ended his tour and he was released. He flew for 12 more years.

Ed had no problem adjusting to coming home. In fact, he went back to Hanoi on the 30th and 50th anniversaries of Vietnam. Walking out of the prison door, he looked around, and thought he would never have done all he has done in the last 50 years had he not been a POW.

Ed had no problem adjusting to coming home. In fact, he went back to Hanoi on the 30th and 50th anniversaries of Vietnam. Walking out of the prison door, he looked around, and thought he would never have done all he has done in the last 50 years had he not been a POW.

He has been to 84 countries and spoken to four million people as a motivational speaker. He has no animosity towards the North Vietnamese. He saw many POWs who were filled with hate and they suffered. Ed says it up to us to decide how we want to live. He says you can’t make him have a bad day and he hasn’t had one since.

Tom Moody joined the United States Army out of high school. His dad wanted him to go to college and become a civil engineer. Tom decided college was not for him and went to the Navy recruiting office downtown. He wanted to be a pilot and the Navy told him he had to have a four-year degree. So, Tom went to the Army recruiter. They had an opening for military police. After some time, Tom decided he didn’t want to be a security guard and heard the 82nd Airborne needed paratroopers. He worked his way up and joined the 1st Army Aviation Battalion, was a part of the Rangers, went to jump school, and OCS school. He went through flight school and became a helicopter pilot. He was the only Sergeant who was Airborne Ranger qualified.

Tom Moody joined the United States Army out of high school. His dad wanted him to go to college and become a civil engineer. Tom decided college was not for him and went to the Navy recruiting office downtown. He wanted to be a pilot and the Navy told him he had to have a four-year degree. So, Tom went to the Army recruiter. They had an opening for military police. After some time, Tom decided he didn’t want to be a security guard and heard the 82nd Airborne needed paratroopers. He worked his way up and joined the 1st Army Aviation Battalion, was a part of the Rangers, went to jump school, and OCS school. He went through flight school and became a helicopter pilot. He was the only Sergeant who was Airborne Ranger qualified.

He was part of the Aviation Battalion at Ft. Bragg, renamed the 118th Air Assault Unit. This unit was first into Vietnam. Tom received the Soldiers Medal for Heroism in 1970 for the following incident.

Tom was flying the command and control helicopter above the landing zone on a mission to transport troops to a particular opening with jungle on both sides. One helicopter was there to disperse smoke to protect the troops from being seen and shot at. This helicopter ran into a tree, tipped over and caught fire. Tom landed his helicopter close to the wreckage. He ran into the fire, grabbed the pilot, and carried him 50 yards to his helicopter. He went back for the crew chief and carried him over his shoulder. He transported the pilot and crew chief to medivac and they survived.

Tom was flying the command and control helicopter above the landing zone on a mission to transport troops to a particular opening with jungle on both sides. One helicopter was there to disperse smoke to protect the troops from being seen and shot at. This helicopter ran into a tree, tipped over and caught fire. Tom landed his helicopter close to the wreckage. He ran into the fire, grabbed the pilot, and carried him 50 yards to his helicopter. He went back for the crew chief and carried him over his shoulder. He transported the pilot and crew chief to medivac and they survived.

Tom spent 39 months in Vietnam! After his first tour, the Army sent him back to the U.S. and told him he was going to Germany. Tom said he wanted to go back to Vietnam. After the second year, the Army sent him back to the U.S. and again told him he was going to Germany. Tom said he still didn’t want to go to Germany and wanted to go back to Vietnam. That third tour was extended three months.

During his first tour, the helicopter door gunners, from the 25th Infantry out of Hawaii, only had M14 rifles. The next tour, the door gunners had machine guns. They often coordinated with the Air Force F100s for support. One time Tom was sent up north at Thanksgiving to rescue POWs but they had been moved.

He says they did what they were told to do, didn’t ask questions, and didn’t know the big picture. They were there to support their brothers. In retrospect, Tom thinks the U.S. government got us into a war we shouldn’t have gotten into. We lost over 50 thousand men. Their hands were tied, because they couldn’t shoot unless shot at.

Out of 7000 helicopters in Vietnam, 3000 were destroyed. Eleven hundred helicopter pilots lost their lives and 1,200 crew were killed. From start to end, 100,000 pilots and crew served in Vietnam.

After Tom retired, he owned a well-known boating business in Destin. He is a humble and generous man who enthusiastically acknowledges the contribution and bravery of others. He has been named Crestview’s Citizen of the Year.

This year the Greater Fort Walton Beach Chamber of Commerce will be hosting “Honoring Our Heroes,” a tribute to our Vietnam veterans on the 50th anniversary of the end of the war. The April 28-30th event will be filled with historical presentations, panel discussions, and a banquet featuring distinguished speakers. The event is open to the public, with free admission to the educational programs on April 28-29. Ticket information for the Heroes’ Tribute Banquet on April 30 is available online at FWBchamber.org.